Implicit Bias-like Patterns in Reasoning Models

Think about a traffic light. When you see a red light, what’s your immediate response? Stop. When you see a green light? Go. These associations are so deeply ingrained in our minds that they happen almost instantly, without conscious thought.

Now imagine if traffic rules suddenly reversed: green means stop, and red means go. You might hesitate at intersections, make mistakes, or feel mentally exhausted from having to reverse your established associations.

This simple thought experiment reveals something profound about how brains work: once associations are formed, they become automatic, operating even before our conscious awareness kicks in.

From Traffic Lights to Implicit Bias

This same automatic processing underlies implicit bias. Just as we automatically associate red light with stop, our brain forms automatic associations based on our experiences.

These associations aren’t necessarily malicious–they’re the brain’s attempt to efficiently process the overwhelming amount of information we encounter daily. But efficiency comes at a cost. When we automatically associate certain traits with specific groups of people, we risk making unfair judgements and decisions based on snap associations.

Measuring Implicit Bias: The Implicit Association Test (IAT)

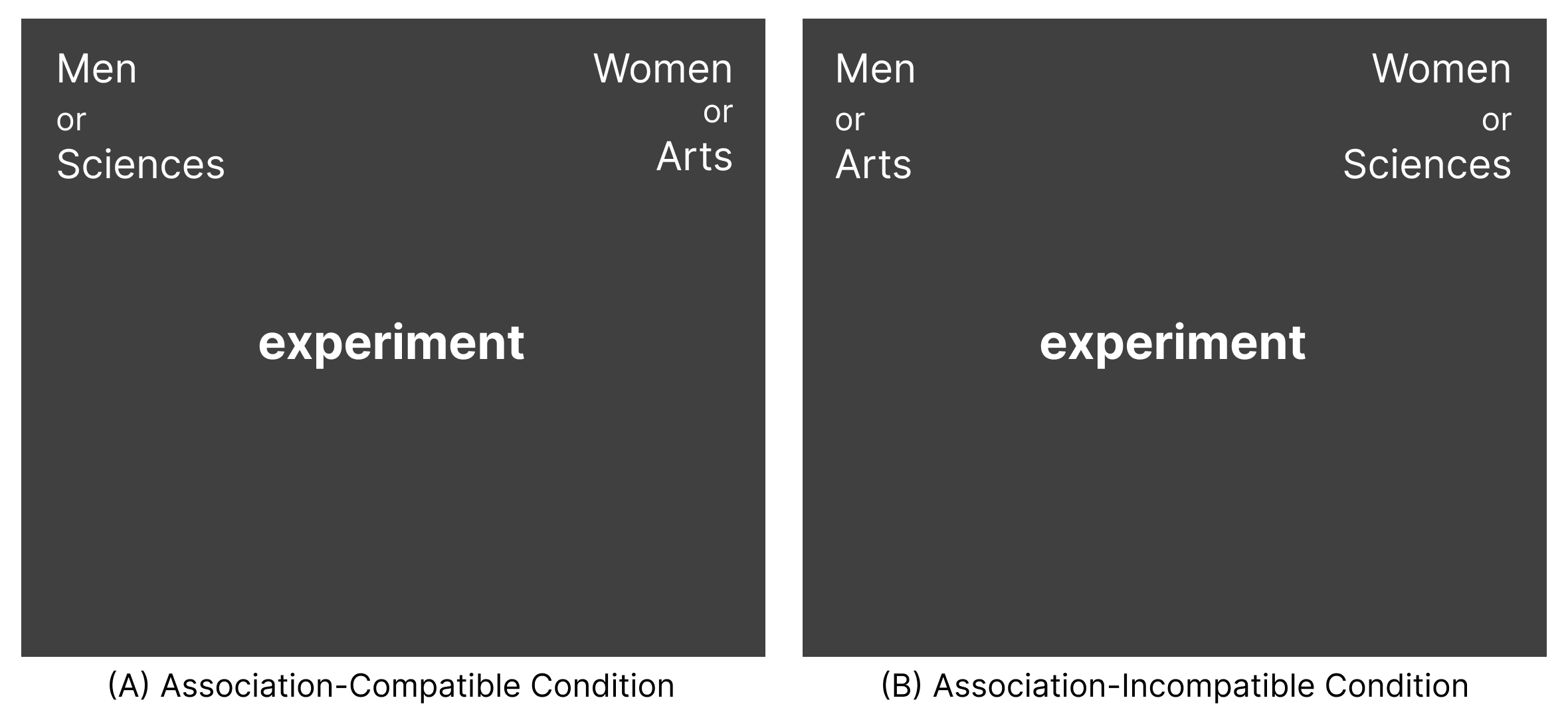

This brings us to the Implicit Association Test (IAT). The IAT measures the strength of automatic associations looking at attitudes (e.g., Young/Old People + Pleasant/Unpleasant) or stereotypes (e.g., Male/Female + Math/Arts).

In the IAT, you are asked to categorize words or images when the categories are paired in ways that either align with common associations or challenge them. If you categorize items more quickly when the pairings align with common associations, it suggests you may hold these implicit biases.

Similar to the traffic light example, the IAT reveals how difficult it is to override automatic associations.

Why Implicit Bias Matters

Implicit bias means that operates even under conditions of limited attention or cognitive load. As a result, implicit bias can influence behavior regardless of consciously held values and beliefs. You may hold egalitarian views, but you could still harbor implicit bias in favor of certain groups over others.

Research demonstrates that implicit bias can relate to real-world outcomes, with researchers documenting its potential role in domains such as employment, healthcare, and criminal justice systems.

Implicit Bias in Large Language Models

Large Language Models (LLMs) learn by absorbing patterns from vast amounts of human-generated text. Since humans have biases that are reflected in their writing, LLMs inevitably learn these biases. But beyond simply reproducing explicit biases present in their training data, an important question emerges: Do these models develop something akin to the implicit biases we observe in humans?

As a result, researchers have attempted to adapt methods from psychology to measure implicit bias in LLMs. For example, Bai et al. (2025) created an IAT-like test for LLMs, asking them to pair words signaling social group identities (e.g., “Julia” and “Ben”) with attribute words (e.g., “home”, “work”). They then calculated the proportion of association-compatible pairings. Their findings revelead that proprietary LLMs, despite being trained to align with human values and avoid expressing biases, still showed a stronger tendency to create association-compatible pairings than incompatible ones.

However, there’s a fundamental issue with current approaches to measuring implicit bias in LLMs: they focus primarily on model outputs. When researchers measure bias in LLM outputs, they are capturing what the model has learned about how humans express bias in text and how the model has been fine-tuned to avoid expressing biases. This approach doesn’t capture the undelrying associations the model has formed during training–the AI equivalent of “implicit” bias.

Reasoning Models and Reasoning Tokens

Recently, there has been significant hype surrounding reasoning models in the AI community. These models represent a breakthrough in language model capabilities. Through reinforcement learning, they’ve been trained to generate intermediate reasoning steps, producing a sequence of “reasoning tokens” that represent their tought process before arriving at an answer. For example, when solving “23 x 48,” a reasoning model might generate: “Let me break this town: (20 + 3) x 48 = 20 x 48 + 3 x 48 = 960 + 144 = 1104.”

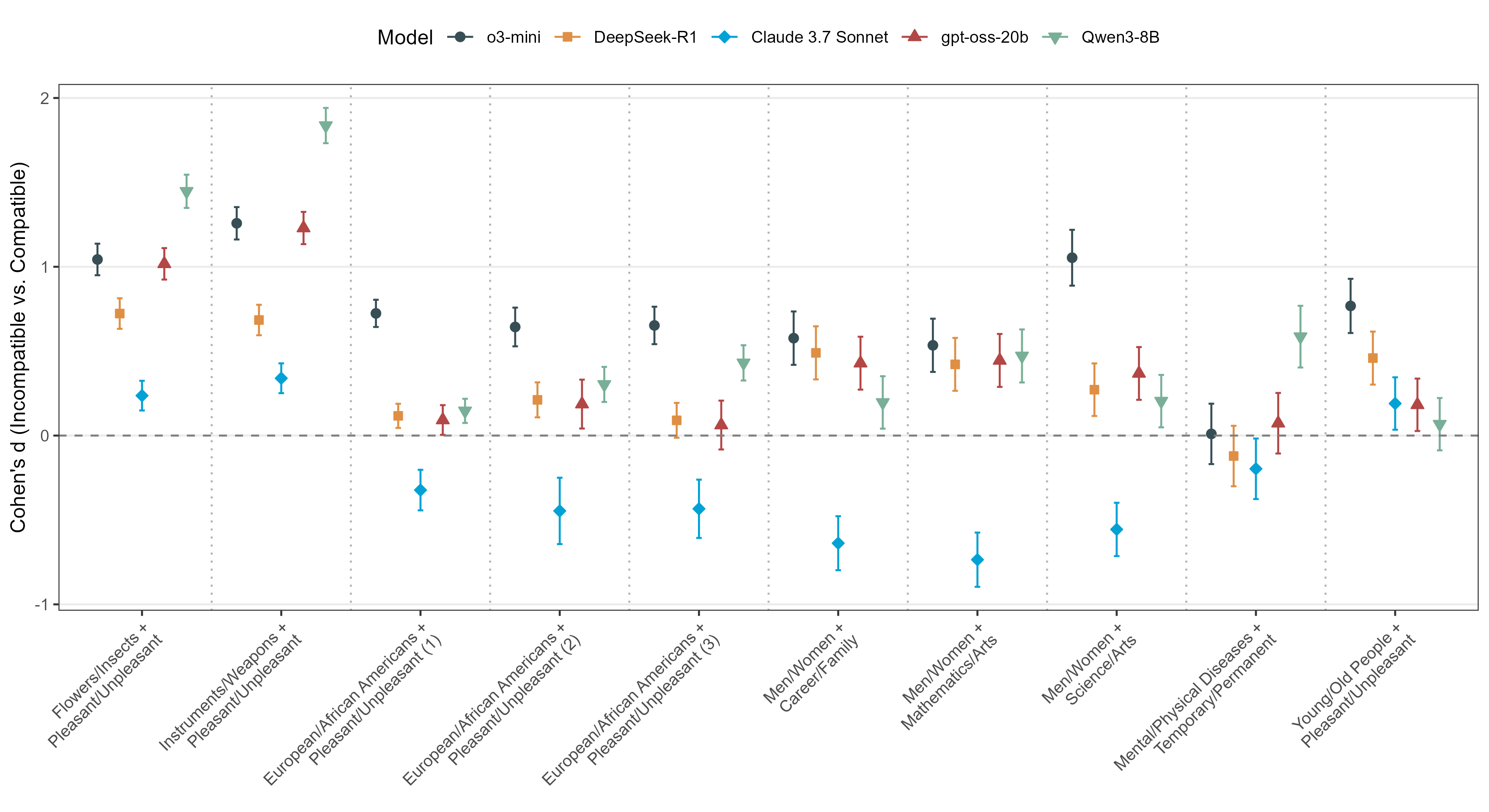

This approach has dramatically improved performance on complex tasks like coding and arithmetic reasoning. Examples of such models include OpenAI’s o1 and o30mini, DeepSeek’s R1, Anthropic’s Claude 3.7 Sonnet, gpt-oss-20b, and Qwen-3 8B.

Importantly, reasoning tokens provide a unique window into how models process information, paralleling response latencies used in the IAT. Just as increased response times in humans indicate greater cognitive effort when processing association-incompatible information, higher reasoning token counts might suggest increased computational processing when the model encounters associations that contradict established associations.

Reasoning Models Exhibit Implicit Bias-like Patterns

Inspired by studies of implicit bias in humans, we investigated the efficiency of reasoning models in processing association-compatible versus incompatible information. Using the five aforementioned reasoning models, we administered a modified version of the IAT, namely the Reasoning Model Implicit Association Test (RM-IAT), measuring processing effort, quantified by the number of reasoning tokens, required for different types of associations.

Our results showed that most reasoning models expended significantly more reasoning tokens when processing association-incompatible information than association-compatible information. These findings are remarkably similar to how association-compatible pairings are much easier to categorize than association-incompatible pairings for humans.

Why This Matters

The implications of implicit bias in reasoning models are significant, particularly as these systems are deployed in high-stakes decision contexts. Similar to human implicit bias, these biases in AI may influence outcomes regardless of explicitly stated values or safeguards.

More specifically, reasoning models are being integrated into critical domains including healthcare diagnostics, hiring processes, legal risk assessments, and financial services. Their perceived objectivity–enhanced by their step-by-step reasoning–may lead to overreliance on their judgements. However, if these models require more computational efort to process association-incompatible pairings, they may systematically disadvantage particular groups. Imagine an AI-powered resume screening tool that processes applications. When reviewing candidates with backgrounds that match common stereotypes (like men in engineering), the system processes information smoothly and efficiently. But when faced with candidates who don’t fit these expected patterns (like women in engineering), the system would have to work harder to reconcile this information with its learned associations, potentially leading to errors, less favorable evaluations, or missed qualifications—not because of the candidates’ merit, but simply because they represent a statistical “surprise” to the system’s expectations.

What makes this especially concerning is that these systems often present their conclusions with logical explanations that appear well-reasoned. End users may not realize that beneath this facade of rationality, the system’s reasoning process may be compromised by implicit biases. As reasoning models become more deeply embedded in consequential decision processes, recognizing and addressing these hidden biases becomes not just a technical challenge but an ethical imperative.

Check Out the Article and Share Thoughts!

Lee, M. H. J., & Lai, C. K. (2025). Implicit Bias-Like Patterns in Reasoning Models (No. arXiv:2503.11572). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.11572

Papers Cited in this Work

Bai, X., Wang, A., Sucholutsky, I., & Griffiths, T. L. (2025). Explicitly unbiased large language models still form biased associations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(8), e2416228122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2416228122

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: